"On the downside, the Chinese come with their own styles"

Africa is at the centre of our publishing programme this year: Its cities are the fastest growing in the world, which brings many challenges. Remy Sietchiping, from the UN, is an expert on the urbanisation of the continent. An interview on Chinese infrastructure, the perils of glass façades, and cities as engines of democratisation.

Interview: Björn Rosen

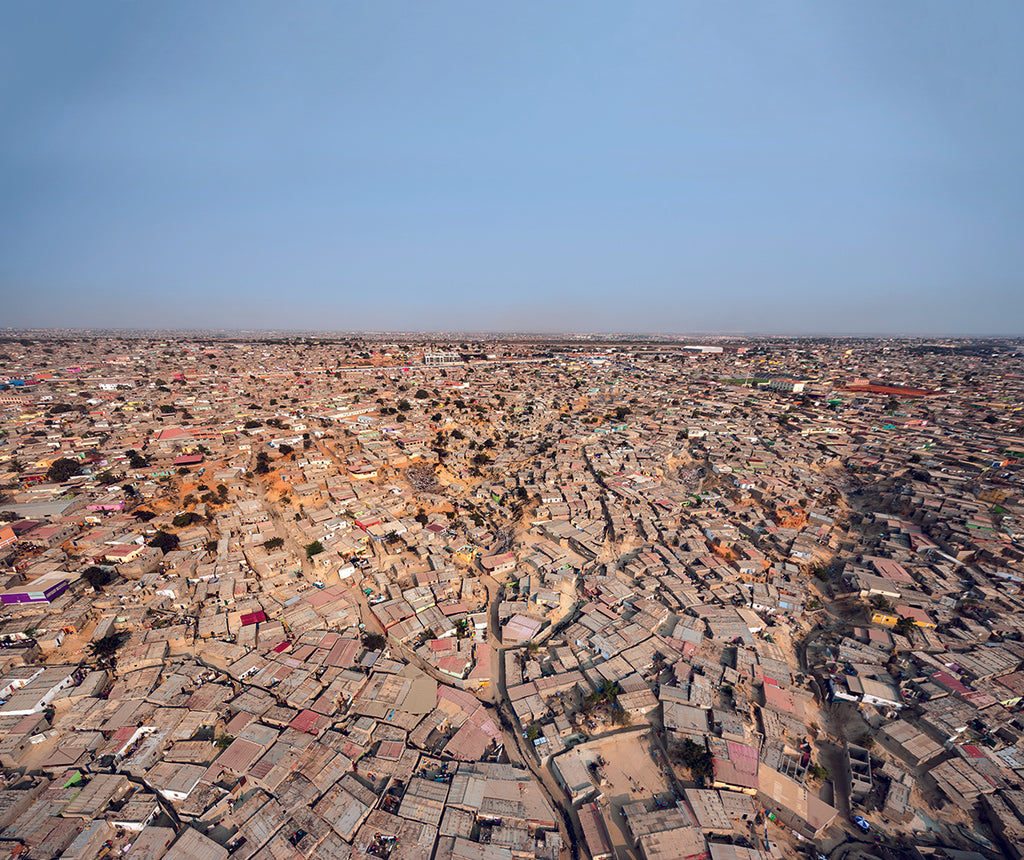

Photo: Informal constructions house the majority of Angola's population, © K. Luchansky

According to the World Bank, urbanisation is the single most important transformation that the African continent will undergo this century. Cities in Africa are the fastest growing in the world, and Lagos, Nigeria, is projected to become the largest city on earth by 2100, with 88 million inhabitants. Is this development stoppable?

No. People have always migrated throughout history. It’s part of human nature, and no policy or intervention can stop this behaviour in a democratic context. This is in fact a good thing. Developing countries usually have a higher percentage of their population living in rural areas. It seems that nations cannot really start being seen as emerging economies until they reach 50 per cent urbanisation.

Africa is currently still the least urbanised continent. But it also lacks an industrial sector, unlike recently emerging economies such as India, China, and Brazil.

I don’t expect Africa to take the same path towards urbanisation. Of course, industrialisation is a lever of change, but it is not the only one. Cape Verde, for example, has a high human development index and a relatively high GDP, yet it has zero industry. Rwanda is also emerging, but not based on industries. I should also emphasise that the African continent is very diverse, and it is crucial to consider the nuances. Some countries are highly urbanised, others are not. Going back to Cape Verde: this is a small island country, where the majority of people live in urban areas. Meanwhile, in Namibia, people are highly concentrated in certain areas, while large parts of the country are almost empty.

Africa’s population is rapidly growing. How much of its urbanisation is simply due to the higher birth rates?

That’s certainly one factor. The situation is far different from Europe, where birth rates are low and some cities are even shrinking. But another – often overlooked – reason is that life expectancy has been increasing in Africa over the last 30 or 40 years. Moreover, many villages or peri-urban areas are being agglomerated into urban areas. And, of course, people are moving from small rural towns and villages to bigger settlements.

This also leads to the growth of slums. On the upside, an article in Foreign Affairs recently argued that urbanisation is an ‘engine of democracy’ and that denser social networks make it easier to organise protest.

To some extent. Recent revolutions and protests all happened in cities, from the Arab Spring in Tunisia to the protests in Sudan. However, this is more a phenomenon of dense neighbourhoods where people feel that their fundamental rights have been violated. Those who live in posh neighbourhoods don’t necessarily feel the urge to take to the streets.

What can architects do to better manage African urbanisation?

Cross-sectoral collaboration is still largely underexplored in Africa. Architects often design a space without considering its impact on the city, region, and nation. This is a shame, because working with sociologists, anthropologists, and health practitioners can significantly boost creativity and innovation. Diverse viewpoints from different disciplines are crucial for understanding how society works. I also think African architects could be more careful about adopting other building cultures. It often makes no sense to build with a lot of glass. The material forces you to rely on air-conditioning, which is costly and certainly avoidable if you adapt your building methods to local conditions. It is unfortunate that the use of local materials is widely seen as a somehow inferior approach.

Another major trend in Africa is the growing engagement of Chinese developers, who are building infrastructure all over the continent. Is this a positive trend?

Chinese investment has led to both improvements and concerns. Developers from China complete projects on time and rarely revise the budget. Working with Chinese developers is appealing for many African countries because the financing is easy. The interest rates are attractive, and you can pay with natural resources instead of cash. Chinese investment has enabled much of the business infrastructure built in Africa in recent years. So there are many positive aspects. On the downside, the Chinese not only come with their own architectural styles, they tend to bring everything else required for the construction: tiles, doors, finishings – even parts that could be produced locally. Moreover, the architectural plans and maintenance manuals are all in Chinese. I have noticed during trips to China that the materials there are sometimes of a much higher quality than what I see in Africa. Finally, the contracts are prepared by the Chinese developers, and the countries often just sign them.

What about the rural regions that are being abandoned due to urbanisation? Do they need more attention?

Urgently. But so do the smaller cities, especially because they are more manageable. Early intervention enables you to attract investment and create the kind of city you want. If towns become more attractive, people won’t always want to flock to the major cities. This leads to a more balanced kind of development, with services and functions evenly spread out throughout the country instead of concentrated in one area. Rwanda is a positive example. The Rwandans make sure that the smaller towns have a clinic, a school, or another particular urban element that shapes the identity of the place.

REMY SIETCHIPING is a Nairobi-based representative of UN Habitat, the United Nations programme for human settlements and sustainable urban development. Born in Cameroon, he holds a PhD in Geography from the University of Melbourne. He has contributed two articles to Architectural Guide Sub-Saharan Africa.

The wait is almost over! After many years of research and preparation, our Architectural Guide Sub-Saharan Africa will be on the shelves in December. It will offer a unique insight into a wealth of buildings that is frequently overlooked in the west.

Strengthening climate resilience in Central Vietnam trough nature-based solutions: Vertical green elements will create a shady and cool public space for school children and residents on hot days. © GCLH

Strengthening climate resilience in Central Vietnam trough nature-based solutions: Vertical green elements will create a shady and cool public space for school children and residents on hot days. © GCLH